The U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Homeland Security Exercise Evaluation Program (HSEEP) includes games as one of their discussion-based exercise types, alongside tabletops, workshops, and seminars. Although tabletop exercises are common discussion-based exercises in a multi-year Integrated Preparedness Plan (IPP), that practice format is not necessarily challenging to participants. For example, public health departments and hospital groups who need to test their response plans continually may go through the motions of “checking the box” on discussion-based exercises. Even with injects and debriefs, there is not an immediate reaction to the planned or discussed course of action implemented as part of the exercise. For public health and hospital officials, this is not their reality, and they may not be challenged to engage the scenario critically with only a tabletop exercise.

Games, especially online command and control (C2) games, offer a different experience for the player, the controller, or the evaluator. The online aspect allows players to participate from anywhere – saving time and money for participant travel and other exercise planning costs. The accessibility to and familiarity with online games allows for “whole community” engagement in significant ways, namely, motivation and engagement. It also provides controllers and evaluators with more elaborate reporting tools, such as players’ responses, delays, and decision-making time. Said reporting tools then can be used in after-action reports to provide quantitative assessments that contextualize survey feedback. This is one way that artificial intelligence is helping public health and other response organizations with their continuity of operations (COOP) and continuity of government (COG), ensuring essential functions are not disrupted across individual organizations and the whole of government, respectively.

Continuity of Operations

The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated the necessity of effective COOP and COG planning. Fulfilling essential functions and protecting vital records and software are essential for public health agencies, but all organizations can benefit from such planning. Using games to exercise COOP and COG plans can provide pathways to assess decision-making, lines of succession, and mitigation measures. One example is the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) Cyber Ready Community Game, a board game that evaluates players’ ability to prepare for cyber incidents adequately. By forcing players to prioritize the protection of specific vital systems (Community Lifelines and Critical Infrastructure) through mitigation techniques, the game attunes participants to how vital system failures can lead to cascading effects for an organization. The Cyber Ready Community Game is a great jumping-off point into gamification. It is cost-effective (free) and has a low barrier to entry; just be sure to have the facilitator(s) play a round beforehand so they understand the rules themselves.

Due to the severe impacts on healthcare facilities and the cascading effects they can cause, cyberattacks are a good example of a threat that can be mitigated through proper COOP and COG planning. The cybersecurity world adopted gamification early on (likely due to the nature of already being part of the virtual environment). In fact, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) uses gaming to identify, test, and reward the federal workforce’s best cybersecurity experts through a nationwide competition. Online C2 games can provide similar benefits to public health and hospital officials.

Challenging and Competitive

Many of these online games are role-playing games that encourage players to think on their feet in decision-tree scenarios. Every decision a player makes – or fails to make on time – progresses the incident scenario so that the players cannot forecast the outcome in advance. Players often must react to unforeseen consequences of their decisions, for example:

- Will a public health clinic flood and have resources destroyed because its location was not considered against the revised floodplain?

- What happens if the cellular network goes down?

- How does a downed network impact interoperable communications systems?

- What happens when a tornado strikes a community during a global pandemic?

- What happens when (not if) a plan goes sideways?

It is critical to monitor and report how quickly the players digest the information they just received, prioritize their objectives, develop courses of action, and communicate their strategy. These are all elements of online emergency management-related games, including those that benefit public health and healthcare. Creative thinking, reactionary decision-making, and short- and long-term strategic planning have been staples of the fantasy role-playing genre. These aspects are coming to healthcare settings, emergency operations centers, university simulation labs offering emergency management degrees, home offices, and consultant or third-party training facilities. Games also generally offer benefits(networking relationships, positive emotions, competitive engagement with co-workers, sense of accomplishment, etc.) to players.

Since its inception, the impromptu aspects of consequence management in C2 have been a staple of TEEX’s IMS650 – Jurisdictional Crisis Incident Management – Incident Command Post resident course at College Station, Texas. These same features can be amplified through artificial intelligence tools to provide a broader spectrum of scenario impacts and perform faster than a human controller or evaluator can re-order a Master Scenario Exercise List.

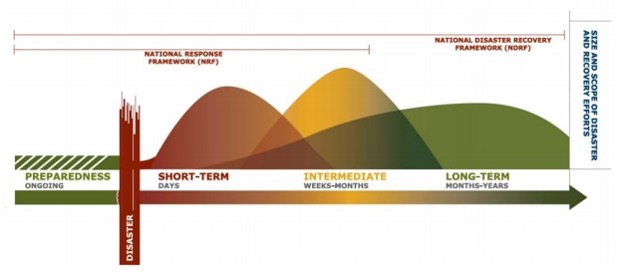

Online gamification can be visual with recorded snippets of videos, text-driven, or even completely animated. The games can be built on any hazard or threat and, of course, incorporate complex scenarios. Games do not have to be too elaborate or expensive to generate. Although they tend to be response-phase oriented, they can be designed for any or all cycle phases (see Fig. 1). The success of a game – including potentially added wellness benefits to the players – will be more robust than a tabletop, in terms of exercising the plans, organization, equipment, and training. And games can have built-in feedback loops to be self-enhancing, through artificial intelligence.

Some additional aspects of the fantasy role-playing genre that public health, hospitals, and other response organizations can consider include:

- Dice Rolls and Wheel Spins – Dice rolls and wheel spins are often used in role-playing games to add randomness to the game. In much the same way a simulation cell (SimCell) may randomly determine the success of an action, online and in other games, this randomizer can be built in. Adding randomness to an exercise can have interesting outcomes, forcing participants to overcome challenges they may not have anticipated.

- Magical Powers – The strengths and capabilities of an organization coming into a multi-player game (with different organizations, some having overlapping skills) are usually established before a game commences (and often align with their real-world strengths and capabilities). For example, if a fire department has 25 firefighters and three apparatus vehicles, that may be how they begin the game. Online games can be coded to encourage mutual aid, penalize for it, or both. Scoring and available resources can be enhanced when participants perform cooperation, coordination, collaboration, and communication activities. The same enhancements can occur when real or notional players use whole-community partnerships in the game, depending on the game’s design.

- Open World, Many Decisions – Public health and other response organization role-playing games have an overarching mission the players must complete. However, players may encounter dozens of side missions they can perform on their game journey, possibly distracting them from their stated goal. An exercise scenario with many components within the incident (and no direction from the facilitator or controller on where to start) challenges players to size up the situation and prioritize their objectives in more natural ways than other discussion-based exercises. For example, a complex coordinated terror attack scenario could include impacts on multiple critical infrastructure systems, forcing players to collaboratively discuss the Community Lifeline system they must first address and why. Watch how quickly unity of effort

- Put Away the Plan…Sort Of – In the strictest interpretation of the HSEEP goals, exercises test more than the players and their knowledge of the plans in play. It also exercises the systems and tools (the equipment) needed – especially for C2 – and the previous training that needs exercises and evaluation. In an online game, the imagination of the players and facilitators or controllers (i.e., game masters) is often the only limit to what can happen. This design can lead to wild, out-of-the-box tactics but also pushes players to generate creative solutions to the problem. Thanks in large part to the global pandemic of COVID-19, many public health and emergency management plans were dismissed out of an abundance of caution. As long as players remain within the game’s framework and are realistic about their roles and responsibilities, nontraditional tactics can be implemented successfully. Whether this leads to unexpectedly better or significantly worse outcomes, the essential factor is testing players’ abilities to identify critical decision-making points, think through possible consequences, and implement strategies.

As public health, healthcare, and emergency management organizations embrace artificial intelligence more, they should also consider its use in online games. Such role-playing games have significant benefits – including those with roguelike aspects – for training and exercising plans, organizational constructs for response, recovery, and the other phases of a disaster, the equipment and systems used, and the training of all involved. As grant budgets get tighter and the cost of manpower and materials rises, games can provide a cost-effective option to evaluate decision-making during a response. These visual scenarios engage participants differently than tabletop exercises, provide immediate and post-exercise evaluation, and can be as simple or complex as is needed to achieve the exercise objectives. For these reasons, gamification is not just the future of the profession, but the current reality of public health and emergency management.

Listen on

Michael Etzel

Michael Etzel is an Associate Emergency Manager and an Emergency Management Specialist Trainee with the Nassau County (NY) Office of Emergency Management (NCOEM). Michael is primarily assigned to the office’s planning section, where he coordinates planning projects, assists in training and exercise development, and serves as the NCOEM liaison to the Nassau County Fire Commission’s Emergency Management Committee. A graduate from St. John’s University with a B.S. and M.P.S. in homeland security, Michael is currently pursuing a doctoral degree. His research interests include domestic violent extremism, community resiliency, and emergency management theory.

- Michael Etzelhttps://domprep.com/author/michael-etzel

Michael Prasad

Michael Prasad is a Certified Emergency Manager®, a senior research analyst at Barton Dunant – Emergency Management Training and Consulting, and the executive director of the Center for Emergency Management Intelligence Research. He researches and writes professionally on emergency management policies and procedures from a pracademic perspective. His first book Emergency Management Threats and Hazards: Water was published by CRC Press in September 2024, and his second book Rusty the Emergency Management Cat is now available on Amazon to assist emergency managers in communicating with families to help them alleviate disaster adverse impacts on children. He holds a B.B.A. from Ohio University and an M.A. in emergency and disaster management from American Public University. Views expressed may not necessarily represent the official position of any of these organizations.

- Michael Prasadhttps://domprep.com/author/michael-prasad

- Michael Prasadhttps://domprep.com/author/michael-prasad

- Michael Prasadhttps://domprep.com/author/michael-prasad

- Michael Prasadhttps://domprep.com/author/michael-prasad